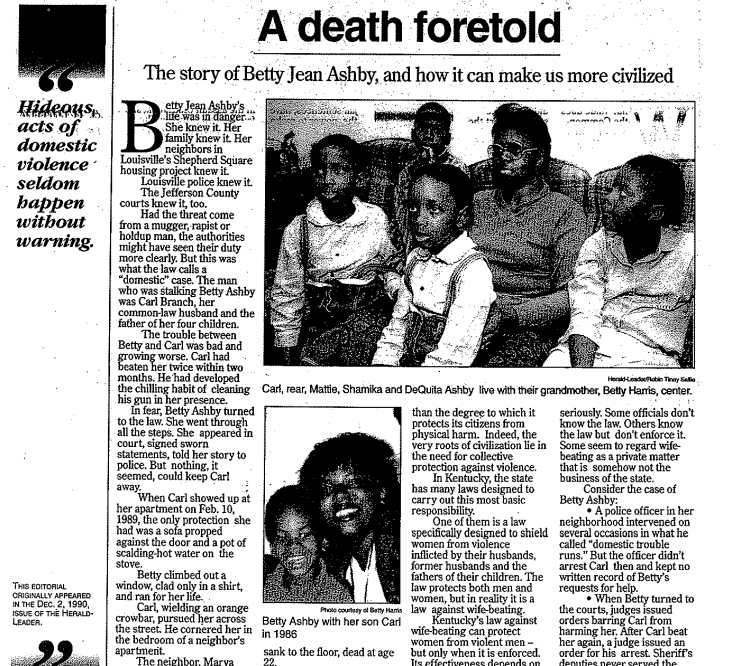

Maria Henson was a editorial writer for the Herald Leader of Kentucky in 1991 when she exposed a systemic failure of Lexington law enforcement and government to protect habitually abused wives from their husbands. As the articles present, these were women who had gone by the book in seeking out help from authorities, taking every single measure they could find to try and secure protection, to no avail. Police were often lackadaisical in their responses to domestic violence to the point where she said they put a search out for a husband carrying a crowbar with intent to kill his wife that carried roughly the same weight as neighbors playing loud music.

Henson was faced with a difficult dilemma after interviewing the surviving abused wives which was whether to use their real names in her editorial articles. As my earlier post quoted from Henson at the event,

“I wondered, if I put these women’s names in the paper, am I putting them in danger?”

She said that at the time she suffered from nightmares of women being abused and killed, and wrestled with the issue through the sleepless nights. This was a time when in newsrooms across the country, reporters and editors were debating whether withholding names did more harm than good for victims of sexual assault. Yet in the end, she decided to include all the correct information and names and it had an immediate effect. Besides winning the Pulitzer Prize for Editorial Writing, in 1992 every single legislation that Henson’s column recommended was passed in Kentucky’s legislature.

I was lucky enough to speak with Henson over the phone several days after the event and I asked about her ethical thinking process regarding the editorial series and her ultimate decision to name sources in the series. She said that ironically enough, when she was applying for the Nieman Foundation fellowship, one of the first questions she was asked was to recount a ethical dilemma she had faced, a question that gave her long pause when thinking about this particular issue.

Henson said that she and her colleagues grappled for a long time with the decision of whether or not to name names when related to the victims of domestic abuse. She indeed did fear what might happen to her sources, in addition to the trauma they were already inducing by asking them to relive painful experiences, in the way of retaliation. That’s why Henson said that in the end, after much serious deliberation, they decided to give every named source the option of killing the story if they felt too afraid or threatened with what might happen to them when it did.

“We were always striving to be sensitive to the sources and any potential danger for them. We did give them unusual control in the publishing process. It was our way to balance presenting powerful, persuasive accounts with real names and real photographs on editorial pages, which was not the norm at the time by any stretch, with being sensitive to women’s fears about sharing their stories.”

And yet out of the many women whose stories were published, not one came forward in protest and even more incredibly there was not a single instance of retaliation against any of the victims named that Henson was aware of.

Henson also said that she tried to be as considerate with her sources as possible while also retaining journalistic integrity, which meant following up on every account she was given (discipline of verification). She fact-checked all claims made to the best of her ability, gathering as many medical and police records as she could find (because in some circumstances there weren’t even records of court proceedings and other official matters).

As Henson explained it, in the end it simply came down to this: this was a rampant issue across the state of Kentucky that everyone knew about but nobody was talking about, and it would take these highly personal and graphic accounts to make a truly lasting impact. And it did: domestic violence laws changed to expand protective orders and protections for battered women, and court practices in these cases improved, along with training for prosecutors and judges.

Therefore her rationale was that risk of harm to her sources by including their names would be overwhelmingly outweighed by the potential for real legislative and systematic change that could only happen if the stories were personal, gripping and raw. Simply saying “a woman who chose to remain off the record” wouldn’t carry the same meaning as an actual name. It was therefore Henson’s hope that the end would justify the means and save lives (teleological or ends-based approach). Her sources were at risk of course, but she also had to think about the entire female population of Lexington and their well-being. If she put one or two women at risk to save thousands of lives in the present and future, it would be the right choice. But instead of just abjectly deciding to print the names with no more discussion, she and her colleagues came up with a more moderate plan that would provide the sources with some autonomy over their accounts (Golden Mean concept, favor the most stakeholders).

In her ethical decision-making process, two main journalistic principles were in conflict with each other: that of minimizing harm and that of protecting the truth to the highest extent. And even with her extra measures to give her sources an out if they felt they needed it, there was still a possibility of harm. Her options were either to publish as unnamed sources and risk lower impact/yield, or print the names and risk harm to the sources. In the end she chose the latter and that is the choice I too would have to agree with personally.

Sometimes the very sources we rely on as journalists can be put at risk just by talking to us. But it’s very important that we tell their stories in the press to as detailed an extent as we possibly can, because it is only through the power of the pen to invoke compassion and empathy that true change can be achieved in many of these scenarios. It is our duty as journalists to report all the facts and not hold back, to seek the truth and hope that we can influence some change or at the very least start a dialogue in the public sphere. In fact, that was exactly what happened in Henson’s case: there was a dramatic increase in the public conversation about domestic violence, to the point where even politicians seeking office talked about it and were asked about it when they were running for office. All in all, Henson believed she made the right decision, and had I been in her shoes I would have felt exactly the same way.

I would also have had a tough time deciding what to do in reporting this story, and I’m not sure my gut reaction or personal moral compass would point me one way or the other. Journalistically the story was obviously important and needed to be told, and using ends-based thinking the publication of a much stronger story with names attached would potentially do the greatest amount good by highlighting and hopefully eliminating rampant abuse in the state. But, as you mentioned, when thinking of minimizing harm Henson would have to grapple with whether revenge would be sought against any of the women named – the publication of the story with names could end up causing serious harm. I’m glad to hear that no such stories unfolded after printing the story, and that such meaningful change was enacted from Henson’s reporting. I’m also glad the reporting team decided to publish the way they did, and the results speak to that sort of decision. Potentially awful things could have resulted from the piece, but they would have followed already awful events that needed to be told in a transparent and truthful way to open the door for conversation and legal and cultural change.

LikeLike

This dilemma reminds me of the first day of class learning about the trolley problem, which I am now realizing journalist have to face more often than not. Do you harm a few to save many? In this case, I believe Henson made the right decision and fortunately that decision had a great outcome. Getting people to talk about an ongoing but undiscussed issue is a huge part of being a journalist. But I do wonder if the publication had caused harm to any of the women, would it have had the same impact? Would the article have been a movement toward new legislature or just a scandal? This would be the worst outcome and completely avoidable had Henson chose to keep them anonymous. I believe Henson, as well as the women interviewed, weighed all of these pros, cons, and “what ifs” when making the decision to publish names. Ultimately, Henson took a risk. And that risk paid off.

LikeLike

Maria Henson was definitely in a difficult position, but I think she made the right choice in publishing the names. It undoubtedly makes her story more impactful. Additionally something you’ve touched upon in your presentation as well, is the old-aged debate of how journalists and the media should handle graphic photos. In this specific case, I think the editorial team made the right call in releasing those photographs because if the purpose was to tell the stories of the battered women, to improve not only the dialogue but the system on domestic violence as well, the publication is going to need to provide something people cannot turn away from – no matter how hard it may be to look at it.

I completely agree with Olivia that Henson took a risk and that the risk paid off, because it certainly could have gone the other way. Olivia raises an interesting question about what would the impact be if the alternative happened and as much as I hate to say it, I would probably argue that it wouldn’t have the same impact, especially if the story did cause more harm to the women. I want to be optimistic and say that by seeing this story, and seeing how these women still are living it if not in worse conditions, that it result in the same strides towards new legislature. However, I think the fear would outshadow the bigger issue at hand.

LikeLike

I think what Henson did is absolutely a mature decision that an ethical and professional journalist would and should make. And as someone pointed last time during class that she would kill the story if it turns out someone undergo stressful harm from the society is quite surprising, I think it is a rational decision that a news organization should do to minimize harm and make those women more comfortable about publishing their names on newspaper at the sam e time maintain its profits and reputation. And also it encounters the code of being independent. Because domestic abuse is not only about one family, but it is a matter of the who society. An ethical journalist should always have the highest and primary obligation to serve the public. I believe Henson believed it is a serious social problem that needs public attention, and at the same time, publishing the women’s names would make a huge effect on how this issue would be seen by the general public as well as law enforcement.

I completely agree with Jodie that if the women’s names are not published at that time, it might be a story that people saw and turned over. Luckily nothing harmful happened to these women and the story becomes a big hit. Henson really made a good choice on the story beyond her journalistic professionalism – and it’s a absolutely something we as young journalists should think about if we encounter similar situation, and react professionally, ethically and bravely.

LikeLike

I thought this was a great example to begin class discussions on ethical findings in media practises as intimate subjects often prove to be a troubling grey area for journalists and media consumers. Given your mention of the ‘escape clause’ and Maria Henson’s virtuous promise to respect the abused women of her story, this made me think of another problematic subject to cover – honour killings. Let’s say a writer was reporting on this issue from afar and had the names of subjects who had their lives in the balance, do you think the same principles could be applied? It these subjects of the story had no access to safe spaces (whether abroad or away from the threatening families) and were at risk of further retaliation, could the journalist here follow the same steps? To publish or not? To include names for credibility or to remove for the safety of others?

Take into consideration the geographic distance of being removed from the story, where the writer may be reporting away from the place at stake (such as the Middle East). How would this also play a role in the ethical decision making here? Could the same rights and needs be supported from afar?

I realise this post is filled with more questions than answers, but I just wanted to offer an example that would be a way to perhaps advance the topic at hand, dealing with intimate subjects in a sensitive subject matter. Just something to think about.

LikeLike